24 Nov 2022

The first Slovak cookies guidelines updated

In our June's blog we published 10 reasons why, in our opinion, it was necessary to amend the historically first Slovak guidelines on cookies. Also as a result of this criticism (adopted by the media), the Regulatory Authority for Electronic Communications and Postal Services (the "Regulatory Authority") cooperated with the Slovak Data Protection Authority (the "DPA") and published updated guidelines (available only in Slovak here).

Were our objections accepted?

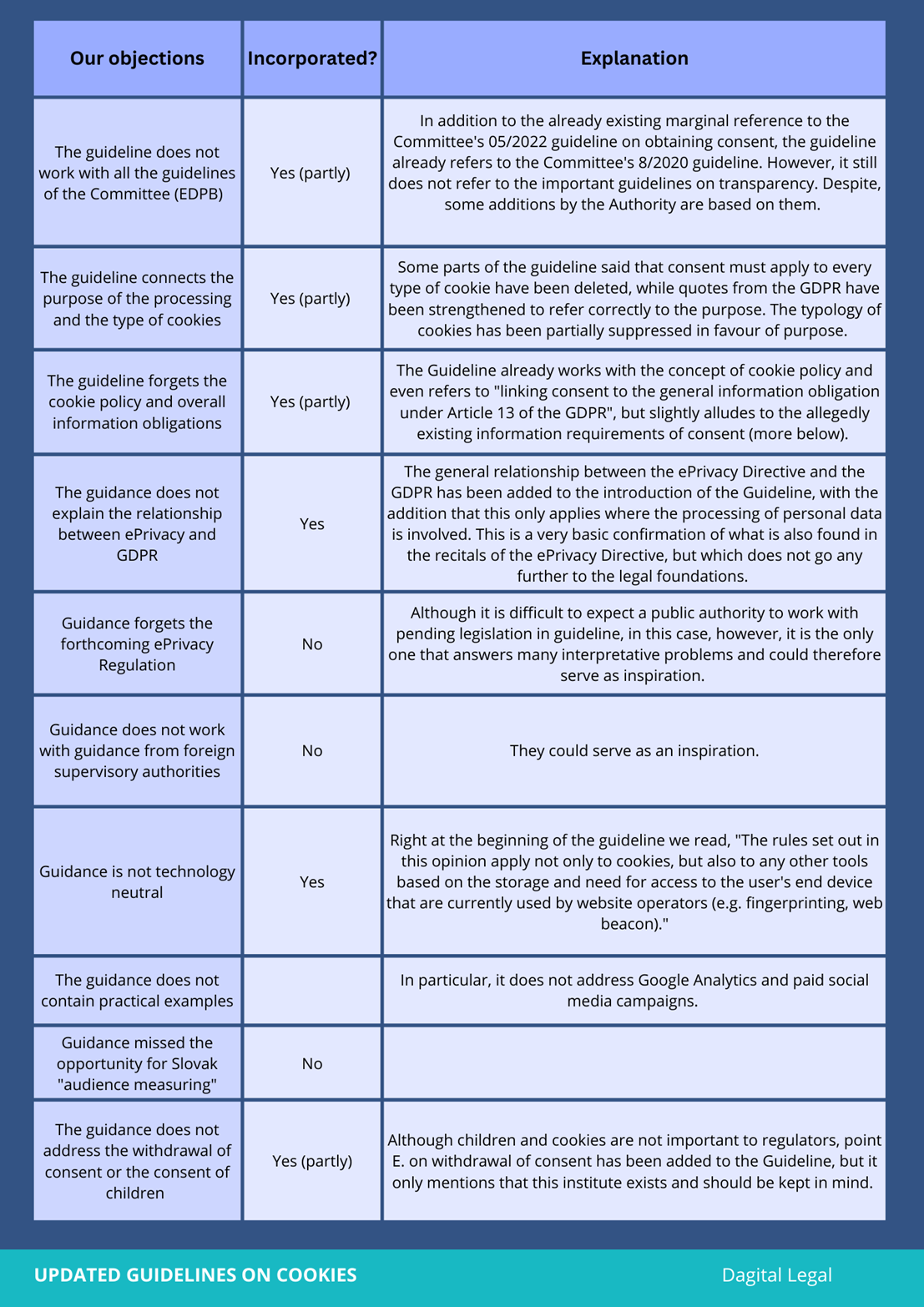

To our surprise, 6 of our 10 objections were accepted and incorporated (at least partially) into the updated guidelines. For a better overview, we prepared the following table.

Which amendments are most significant?

Compared to the the original version, updated guidelines are significantly revised. Within this changes it is however necessary to highlight most significant changes that we also consider positive.

References to GDPR

The most significant and very positive amendment is that after the involvement of the DPA, the guidelines are more in line with the regulatory framework for consent requirements according to the general regulation - GDPR. We specifically highlight the reference to the Recital 17 of the ePrivacy Directive, according to which:

„For the purposes of this Directive, consent of a user or subscriber, regardless of whether the latter is a natural or a legal person, should have the same meaning as the data subject's consent as defined and further specified in Directive 95/46/EC. Consent may be given by any appropriate method enabling a freely given specific and informed indication of the user's wishes, including by ticking a box when visiting an Internet website.“

In other words, whenever the ePrivacy Directive and the Electronic Communications Act (implementing it) refers to a consent, it shall be regarded as the consent under the GDPR. This applies not only to cookies. This is also confirmed by other provisions of the new Electronic Communications Act on unsolicited communications (Section 116), but such reference is absent in the act regarding cookies.

What guidelines do not add is that the same applies in cases where no personal data is collected via cookies or when obtaining the consent from legal entities. These more complicated cases are not addressed by the guidelines and left to be determined by the practice, together with the question of legal basis under the GDPR, provided the GDPR applies.

Typology of cookies

We strongly criticized the originally proposed typology of cookies and the link between the consent and the type of cookies. We asked whether, for example, Google Analytics is an analytical or marketing cookie and how many consents are then necessary to obtain (if each type of cookie requires individual consent). This problematic aspect of the guidelines was partly pushed to the background, but not completely. In several parts, guidelines correctly state that consent shall be obtained for the purpose (as the GDPR requires) and not for the specific type of cookies. However, it still refers to the old typology of cookies and some places. It is possible that this wording is a result of a compromise of slightly different views of the regulators and leaves room for manouvering when setting up the cookie banner.

Another positive change is that the biggest flaw of the original guidelines was removed. Original guidelines stated that necessary cookies do not need to or do not process personal data. This was obvisouly not corrent and is already reflected in the updated guidelines as the problematic part has been removed.

Information obligations

Consent and information obligations under GDPR cannot be discussed separately as these obligations are so interlinked that in practice they are fulfilled jointly. Any references to the cookies policy were completely absent in the original guidelines, which was now corrected. Guidelines now work with references to cookies policy on several places. Even a reference to the general information obligation under Art. 13 GDPR was added. In general, these are all positive changes, however, the confusion between information obligations with consent requirements (see below) cannot be considered a positive change.

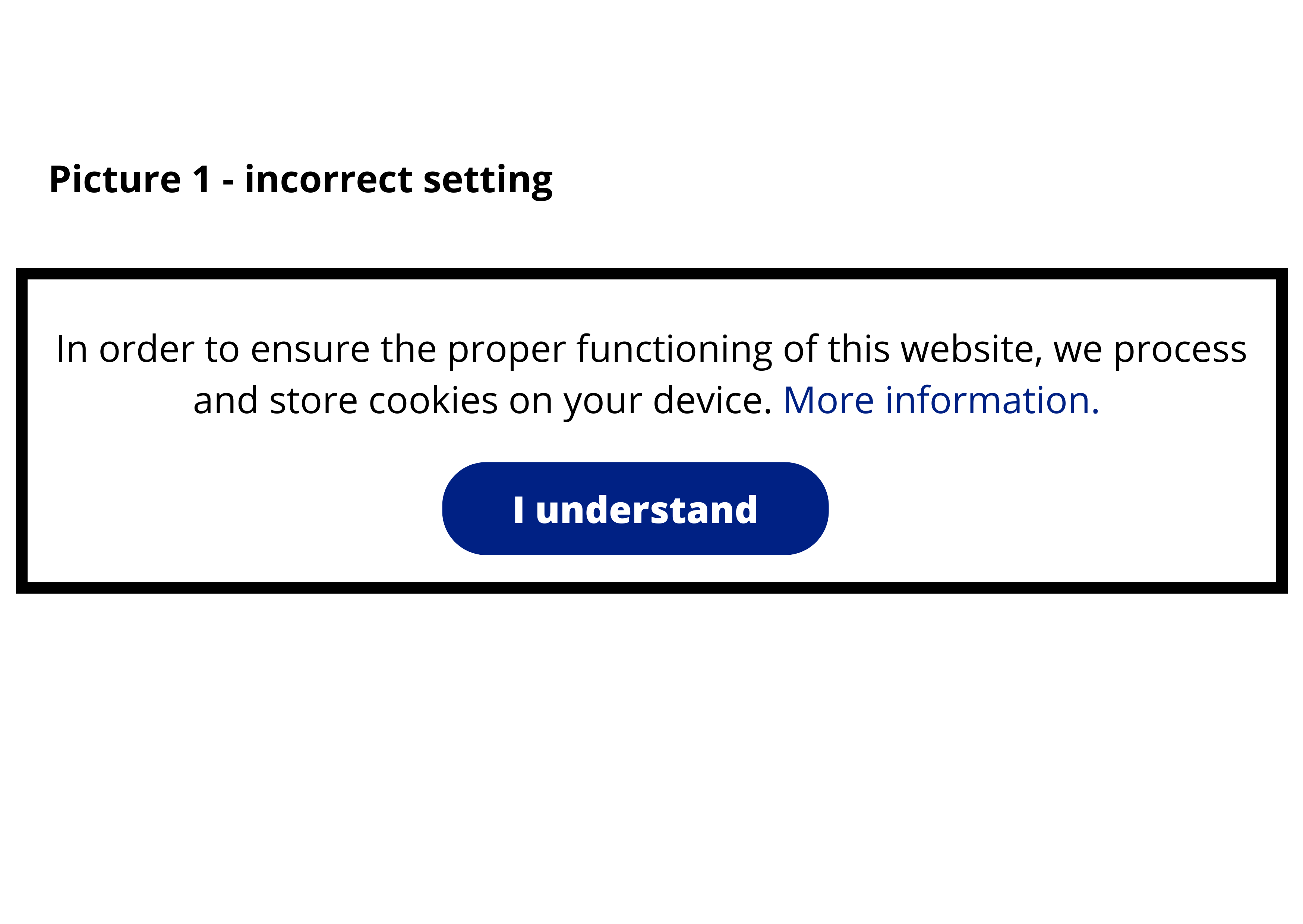

Example No. 1 - example of a wrong cookies consent

Pursuant to the guidelines, this example above is still considered as a wrong example of cookies consent but it has been added (importantly), that this may not always be the case. According to the guidelines, this cookies consent cannot be used if it completely obstructs the website or if clicking "I understand" is mandatory to view the website. In other words, when it serves as a cookie wall. If that's not the case, this cookies consent can be legitimate, only the text "I understand" is not recommended. In our opinion, this cookies consent could also be used legitimately if it could be easily closed (X in the top right corner) and at the same time, the website would process only necessary cookies and thus the "I understand" button would not serve as consent. In that case, the button wouldn't even be needed.

Do guidelines still contain any problematic points?

Unfortunately, two new problematic points were included in the guidelines, with which we are well familiar with from the practice of the Slovak DPA. These points should not overshadow the overall positive impact the Slovak DPA had on the guidelines. However, we cannot agree with these points either. Perhaps, this may be also a matter of differing opinions among the departments of the Slovak DPA, which will be resolved only in further practice.

The same colour of boxes

On page 5, guidelines states that the consent button cannot be green while other buttions are red. This is a well-known and profane opinion, that arose (like many other GDPR myths) by misinterpreting something else the EDPB guidelines 3/2022 try to explain (see point 93):

„This condition can become a challenge to prove, e.g. if users are supposed to provide consent by accepting cookies. Furthermore, data subjects might not always be aware that they are giving consent while they click quickly on a highlighted button or on pre-set options.“

This means that if the consent is displayed prominently and is highlighted compared to other choices, according to the EDPB, it may be more difficult to prove (but not impossible) the validity of such consent, because the user may not be aware that it is actually a consent (!). As confirmed in the first sentence, this primarily concerns the practice of social network providers, which used to "hide" other consents under the highligghted acceptance of cookies. This is also confirmed by the title of the given part of the guidelines named: "Managing one’s consent while using a social media platform". This should not automatically mean that all consent window fields must always be the same colour. Primarily because, in the case of the cookies window, it is completely clear to the data subjects that this represents a consent, and thus it is not a situation to which the EDPB refers above.

If this is to be a general rule of interpretation of any consent, it should be mentioned in the main guidelines of the EDPB on consent and transparency, however, it is not. In these guidelines is it not mentioned that other than the same colours of all fields are prohibited and colours of boxes/buttons are not even discussed there.

We even believe that such a colour distinction can be transparent and help the data subjects to decide easily. Of course, it would be a different case if the colours were intentionally changed to manipulate data subject to grant consent by clicking on the red option, for instance. Purposeful practices with the use of opposite / negative wording are similarly prohibited. In general, deceptive, or misleading use of colour can be one of several aspects that can be considered a "dark pattern". However, we should not make this a general prohibition on the use of different colours.

Requirements of consent vs. Information obligation

Further on page 6, the guidelines state that according to the GDPR, "consent wording" must contain all of the following:

“i) identity of the controller, ii) the purpose of all processing operations for which consent is required, iii) what data (type of data) will be obtained and used, iv) the existence of the right to withdraw consent, v) information on the use of data for automated decision-making according of art. 22 (2) (c), if relevant, i) on the possible risks of data transfer due to the absence of an adequacy decision and, vii) adequate safeguards as described in Article 46 of the General Data Protection Regulation.“

There are no provisions in GDPR requiring such a thing. We know exactly the origin of such misinterpretation. These requirements are mentioned in the EDPB guidelines on consent (page 15 point 64), however, the EDPB does not state that such information must be included in the wording of consent, but data subjects must be aware of such information while granting the consent:

"For consent to be informed, it is necessary to inform the data subject of certain elements that are crucial to make a choice. Therefore, the EDPB is of the opinion that at least the following information is required for obtaining valid consent: ... (then the above list of information follows)"

About the information itself, we have expressed reservations in past, because the type of personal data is not part of the information obligation under Art. 13 GDPR, but only under Art. 14 GDPR. However, this is not important here. What is important is that the GDPR only defines what consent is but does not establish any other content requirements of the consent wording. These were stipulated only by the old and repealed Act No. 122/2013 Coll. while going completely outside the wording of the directive / GDPR. As we are trying to explain to the Slovak DPA in several proceedings (and we are being partly successful), the only substantive requirement of consent is the purpose of processing, because the given expression of will is directed towards it in accordance with Art. 6 (1) a) GDPR. Therefore, the following example would suffice as a valid wording of consent:

"I agree with data processing for purposes of direct marketing as per the Cookies Policy."

All other information must be of course provided but not neccessarily within the text of the consent. Additional information can be provided within the cookies policy or general information obligations on in different layers, as the EDPB transparencz guidelines require. Of course, non-fulfilment of the information obligations impacts the overal imforning of data subject (and may play a role in meeting "informed" consent requirements), but it is not a matter of the textual requirements of the consent. If the necessary information is provided, the above consent is valid even without the additional information in its text/wording. This is also confirmed by the EDPB, the GDPR and, finally, these guidelines, which do not contain this information in any correct examples. No example of consent that directly contains these details can be found in any of the EDPB guidelines either.

It should be noted that the information to be provided to the data subjects according to the GDPR is also regulated in other articles than 13 and 14. As part of the information obligations, it is also necessary to consider that according to:

art. 7 (3) GDPR: " The data subject shall have the right to withdraw his or her consent at any time. The withdrawal of consent shall not affect the lawfulness of processing based on consent before its withdrawal. Prior to giving consent, the data subject shall be informed thereof." which is confirmed also by art. 13 and 14 (2) c) GDPR.”

art. 21 (4) GDPR: "At the latest at the time of the first communication with the data subject, the right referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2 shall be explicitly brought to the attention of the data subject and shall be presented clearly and separately from any other information." (i.e. the right to object to legitimate and public interest as well as the right to object to direct marketing, including profiling)”

art. 49 (1) a) GDPR: "the data subject has explicitly consented to the proposed transfer, after having been informed of the possible risks of such transfers for the data subject due to the absence of an adequacy decision and appropriate safeguards" (applied only to the consent to data transfer - used rarely).

However, information obligations must be strictly distinguished from the content requirements of the consent, which are absolutely minimal (practically only the purpose of processing). Of course, it is also possible to incorporate some of this additoinal information that needs to be provided into the consent wording or into the cookies window, which we often do in practice. This information is however a part of broader information obligations and the transparency principle, not a content requirement or a consent wording. We would like to assume that by "consent wording" the guidelines mean not only the first text layer of the consent text but also any other texts, whether within the privacy policy, cookies policy or the website with which the data subject has the opportunity be informed before granting consent.

However, these are only general information obligations under GDPR. There are also specific obligations only applicable to cookies, as defined by (CJEU - Planet49), according to which the following information must also be provided with cookies:

"the information that the service provider must provide to the user of the website includes the duration of the functionality of cookies, as well as whether or not third parties have access to these cookies."

It follows from the context that it is therefore necessary to provide a list of cookies and their name, together with this specific information, as part of the cookies policy. We believe that such an important judgement should have been mentioned in the guidelines. However, the title of the guidelines makes it clear that it only concerns consent itself. Unfortunately, however, if the guidelines mistakenly combine the content requirements of consent with information obligations, then it is necessary to explain the information obligations as well.

As mentioned above, we assume that under the "consent wording" it is also possible to imagine a cookies policy. We have to imagine that if we don't want to agree to the same content text as is included in the cookies policy.

Conclusion

Admittedly, the updated guidelines are far better than the original version. It is also necessary to welcome cooperation and consultation between the two regulators, which is lacking in practice. We really pay tribute and public praise to all of this. Overall, the guidelines have reached an acceptable general standard (in line with ePrivacy Directive), and the resolution of the more detailed aspects that we inevitably encounter in practice is left for us to deal with. Ultimately, this is an acceptable compromise (for us advisors).

What remains open is the question of the enforceability of cookie rules in Slovakia. The Slovak DPA has so far avoided this topic in its supervisory activities, and the decisions and fines of the Regulatory Authority in this regard are still absent. The overlapping scope of the two regulators is still not resolved and will continue to cause problems to both regulators in the proceedings, even if solutions exist. The best solution would be not to have two but one regulator for ePrivacy and GDPR.

Finally, these guidelines also confirm that the Slovak DPA is a better prepared authority of the two, in terms of expertise and capacity for the enforcement of ePrivacy. Scope of powers and enforcement issues would be completely erased if this agenda fell under the Slovak DPA, which the ePrivacy Directive and GDPR not only allow, but prefer.

In case you you need help with setting-up the cookies, including the cookies policy on your website (or in your application), do not hesitate to contact us.

Jakub Berthoty

Dagital Legal, s.r.o.

Did you like this post?

Similar posts

Prvé slovenské usmernenie ku cookies (a 10 dôvodov prečo ho treba zmeniť)

Úrad pre reguláciu elektronických komunikácií a poštových služieb (ďalej len „Úrad pre reguláciu“) vydal 4. mája 2022 tlačovú správu ku cookies, v rámci ktorej zverejnil aj stanovisko odboru štátneho dohľadu k problematike získavania súhlasu s cookies, už podľa nového zákona o elektronických komunikáciách. Vzniklo tak historicky prvé slovenské usmernenie ku cookies, ktoré však narazilo na GDPR ako kosa na kameň.

What is the current regulation of cookies (memorandum)?

It could be said that the theme of summer 2019 was cookies since both the British ICO and the French CNIL issued a guidelines on cookies. The topic was also indirectly addressed by the Board, which issued the Draft Opinion on the legal bases of contract performance in the context of online services. What do these opinions mean before the arrival of ePrivacy regulation? We try to provide answers in our “cookies memorandum”.

Digital Omnibus - uniknutý návrh Komisie

Po prijatí pomerne veľkého množstva nových predpisov a aktov chystá Komisia EÚ chytá "upratanie" a reformu. Určité zjednodušenie GDPR bolo už viac krát naznačené, ale nikdy nešlo o zásadné alebo výrazné zmeny. Začiatkom novembra však z Komisie unikol na verejnosť pracovný návrh nového nariadenia s názvom "Digital Omnibus for digital acquis". Tento návrh nie je finálny, avšak obsahuje aj zásadné zmeny GDPR, ePrivacy smernice, Data Governance Aktu, Data Actu, DORA, NIS2 ale aj ďalších predpisov. Medzi zmenami sú aj kontroverzné zásahy do GDPR ale aj veľmi zaujímavé a pozitívne zmeny, ktoré pomôžu nášmu regulačnému prostrediu. V tomto príspevku ich v skratke predstavíme.